Pretesting, Prequestions, and Errorful Generation

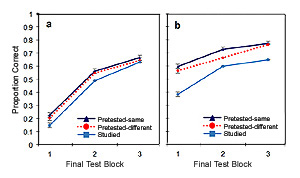

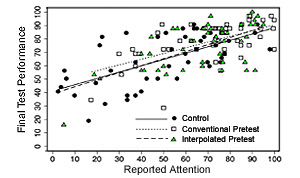

Making guesses about information that one has yet to learn, with those guesses commonly being erroneous (e.g., guessing “Sydney” in response to the question, “What is the capital of Australia?”), can be surprisingly beneficial for learning. This technique is more formally known as prequestioning, pretesting, or errorful generation. Our research on prequestioning has found that it can be as effective as retrieval practice at enhancing memory, and in some cases, even more effective at enhancing transfer, at least for the case of different cue-target combinations (Pan, Lovelett, Stoeckenius, & Rickard, 2019, Psychonomic Bulletin & Review). However, much more about the technique -- including the cognitive mechanisms it engages and its applicability across different learning contexts -- remains to be investigated. We are currently engaged in several lines of research into prequestioning; as summarized below, these include studies of prequestions and mind-wandering, reading of expository texts, and beliefs and practices relating to prequestions and making errors.

How prequestions enhance learning

Our research has uncovered several insights into how prequestioning yields its learning benefits. For example, in Pan, Sana, Schmitt, and Bjork (2020, Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition), undergraduate students received prequestions prior to a video-recorded online lecture and then answered attention probes at multiple points throughout the lecture. Relative to a condition without prequestions, students engaged in less mind-wandering during the lecture and also exhibited better memory for its content on a subsequent memory test. Thus, an important mechanism by which pretesting enhances learning appears to be via changes in attention. Further, in Pan and Sana (2021, Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied), prequestions appeared to change how learners read text materials (that is, they appear to focus more closely on prequestioned content). Those attentional changes may stem from an improved awareness of the information that one has yet to fully master, and better memory for prequestioned portions of the text commonly results.

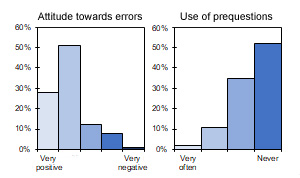

Metacognition regarding prequestions and generating errors

How prevalent is the appreciation for the pedagogical benefits of prequestions, or of making errors more generally? In a multi-site survey of undergraduate students and instructors (Pan, Sana, Samani, Cooke, and Kim, 2020, Memory), half of instructors reported providing materials that can be used as prequestions, but most students do not endorse using them as such. Further, although most respondents recognize that errors are intrinsically valuable for learning, most are unaware of the fact that making errors can have a facilitative effect on memory. Ongoing work is examining whether learners can be prompted to update their beliefs about the efficacy of prequestions through experience. In an initial series of experiments, whereas most participants initially believed that making errors is not as effective as studying without making any errors at all, performance feedback was successful at shifting their beliefs towards a greater acceptance of the utility of prequestions (Pan & Rivers, in preparation).

Interleaved Practice

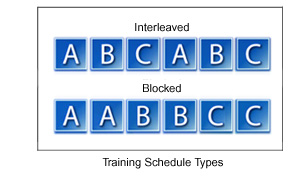

Learning two or more skills or concepts at a time by alternating between them during training (e.g., given concepts A, B and C, using an ABCABC schedule) yields benefits over conventional blocked practice (e.g., using an AABBCC schedule) for motor skills, visual category learning, and math. However, research on educational uses of this technique, called interleaved practice, is still in its initial stages (Pan, Scientific American, 2015). For example, there has been little evidence that interleaved practice benefits language learning. In one the first studies to address this issue, we investigated the effectiveness of interleaving vs. blocking for learning Spanish verb conjugation skills (i.e., specifying the correct verb ending for a given pronoun verb/tense combination in either the preterite or imperfect tenses, as described below). In the first classroom investigation of interleaving in undergraduate physics courses, we compared the efficacy of interleaved versus blocked homework assignments on the acquisition of problem-solving skills (Samani & Pan, npj Science of Learning, 2021). More broadly, questions regarding interleaving that we are interested in include: When is interleaving most effective? What are the cognitive mechanisms that interleaving engages? Using educationally-relevant materials, we aim to find answers to these and related questions.

Interleaving and language learning

In an initial study we explored whether interleaving improves Spanish learners’ ability to conjugate verbs in the preterite and imperfect past tenses (Pan, Tajran, Lovelett, Osuna, & Rickard, 2018, Journal of Educational Psychology). In Spanish instruction, these tenses are commonly confused with one another. Given that interleaving enables learners to contrast categories as they alternate between them, use of the technique may enhance the learning of such materials. Consistent with that prediction, the first successful demonstration of an interleaving effect for foreign language learning was observed. However, not all implementations of interleaving were equally effective: the use of single or multiple training sessions, fixed or random trial patterns, and interleaving throughout most or only during the final stages of training all yielded different results (from no benefit to a large interleaving advantage relative to a blocked condition). This has informed multiple research avenues that we am now pursuing, including the following.

Systematic vs. random interleaving schedules

Does the interleaving effect stem from the unpredictability of training trials, wherein learners do not know which category will be presented next, or other forms of category switching? Again using Spanish tense materials, we found that a systematic pattern which switches predictably between matched exemplars of each tense yielded a large interleaving effect when it was used for study trials, whereas a fully random pattern did not (Pan, Lovelett, Phun, & Rickard, 2019, Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition). Further, a random pattern yielded a large interleaving effect when it was used for practice trials, whereas a fully fixed pattern did not. Overall, these results suggest that the type of interleaving is important when it comes to studying vs. practicing – random interleaving can be a boon to practicing and a bane to studying (with the reverse effects obtained for systematic patterns). In followup work we are investigating whether this pattern generalizes to other types of learning domains and materials.

Retrieval Practice

Retrieval from long-term episodic memory, as occurs when taking a practice test (i.e., retrieval practice), enhances subsequent recall relative to non-retrieval methods. This “testing effect” is robust; for example, it is observed across individuals of diverse memory abilities (Pan, Pashler, Potter, & Rickard, 2015, Journal of Memory and Language). Why does the testing effect occur? Several major accounts posit that tests invoke elaborative processing of information in memory (i.e., the search for a response activates memory for cue words and other related information). If so, then we might expect that cued recall of a word from a triplet (e.g., “gift, rose, ?”) will not just enhance memory for the target (e.g., “wine”); it will also enhance memory for the cue words (e.g., “gift”, “rose”). We investigated this topic across three studies involving word triplets, multi-term facts, and term-definition facts, respectively. In contrast with prevailing perspectives in the literature, testing only enhanced memory for trained targets. This learning specificity—which appears to be a property or characteristic of retrieval practice—occurs with different test formats, amounts of practice, and other training differences.

Specificity of learning following cued recall

The fact that retrieval practice often yields highly specific learning, as demonstrated in three studies (Pan, Wong, Potter, Mejia, & Rickard, 2016, Memory & Cognition; Pan, Gopal, & Rickard, 2016, Journal of Educational Psychology; Pan & Rickard, 2017, Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied), suggests that the testing effect does not rely on elaborative processing. That finding aligns with a recent quantitative model (Rickard & Pan, 2017, Psychonomic Bulletin & Review) of the testing effect. That model posits that testing generates a separate memory of the test event itself (i.e., cue and target) that is distinct from the memory that was formed when information was initially learned. If a different response needs to be recalled, then it appears that this test memory is inaccessible. Further work on this topic includes empirical tests of the model (Pan & Rickard, in prep), plus studies of learning specificity after retrieval from semantic memory (Pan, Lovelett, Stoeckenius, & Rickard, 2019, Psychonomic Bulletin & Review) and for two- vs. three-element stimuli (Rickard & Pan, 2020, Memory & Cognition).

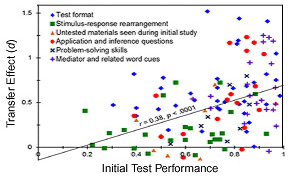

Retrieval practice and transfer of learning

Can retrieval practice enhance transfer of learning from one context to another? In a recent meta-analysis (Pan & Rickard, 2018, Psychological Bulletin), we examined four decades of empirical studies addressing that question. This included contexts ranging from problem solving to application questions. The results showed that tests can enhance transfer (Cohen’s d = 0.40), but not in all cases. They also inform a new transfer model that relies on three moderators: (a) the degree of similarity between the trained and transfer responses; (b) the amount of retrieval success that was achieved during training; and (c) whether either or both of a set of retrieval and feedback techniques—which we refer to as elaborated retrieval practice—were used during training. This review sets the stage for additional transfer research that includes empirical tests of the model, studies of transfer in science courses (Pan, Cooke, Little, McDaniel, Foster, Connor, & Rickard, 2019, CBE – Life Sciences Education), studies of yet other transfer contexts (e.g., analogies), and work on elaborated retrieval practice.

Elaborated retrieval practice, spelling skill acquisition, and more

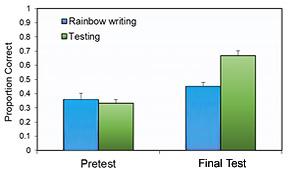

In other retrieval practice work we are examining recall methods that (a) require more than recalling a verbatim response, but involve generating explanations, considering related information, or other forms of elaborative processing; and/or (b) involve post-retrieval feedback that is more than a presentation of the correct answer and includes explanations, abstract principles, or other information (Pan, Hutter, D’Andrea, Unwalla, & Rickard, 2018, Applied Cognitive Psychology). Further, in a line of research on testing and spelling instruction, two controlled studies, the first with adults (Pan, Rubin, & Rickard, 2015, Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied) and the second with 1st and 2nd grade students (Jones, Wardlow, Pan, Heyman, Dunlosky, & Rickard, 2015, Educational Psychology Review), showed benefits for spelling skills. Follow-up work found that adults also benefit from using tests to learn foreign language words. Overall, the results from this link of work inform a historical review of research on spelling tests (Pan, Rickard, & Bjork, 2021, Educational Psychology Review) that exposes contrasts in the literature between test-focused cognitive vs. test-averse psycholinguistic approaches.

Educational and Learning Technologies

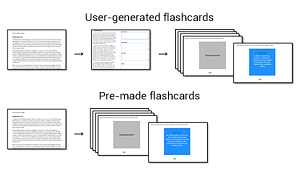

Today's learners are increasingly adopting new ways of acquiring and practicing information. These methods may involve tools obtained online or learning that occurs entirely online. Our research on the utility and consequences of adopting learning technologies is unfolding along multiple avenues. For instance, we have investigated the efficacy of candidate evidence-based learning techniques (e.g., prequestions) on learning from pre-recorded online video lectures (Pan, Sana, Schmitt, & Bjork, 2020, Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition), which are commonly susceptible to lapses in attention. Further, we recently published the first large-scale survey of undergraduate students' uses of digital flashcards for learning (Zung, Imundo, & Pan, 2022, Memory), which established that digital flashcards now exceed traditional paper flashcards in popularity. Additional work has examined the relative efficacy of using pre-made digital flashcards (with content that has already been prepared) versus digital flashcards that require learners to manually add content (Pan, Zung, Imundo, Zhang, & Qiu, in preparation).

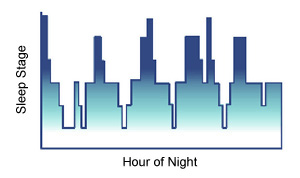

Sleep and Learning

As part of an additional research direction targeting sleep and procedural learning, we published a meta-analysis of sleep and motor skills (Pan & Rickard, Psychological Bulletin, 2015). By performing a meta-regression analysis on a quarter-century of research (88 experimental groups, > 1,200 subjects), we found that, despite what many neuroscience textbooks suggest, there is no evidence for sleep-dependent motor learning mechanisms. Instead, the literature favors a supportive memory stabilization role for sleep (for a follow-up report which arrives at the same conclusions, see Rickard & Pan, Psychological Bulletin, 2017). Further work has also examined publication bias in the sleep and motor learning literature (Rickard, Pan, & Gupta, Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, & Cognition) and the role of sleep in visual texture discrimination learning (Walker, Pan, Modir, & Rickard, Journal of Vision, 2014).

Collaborators

Robert Bjork, University of California, Los Angeles

Elizabeth Ligon Bjork, University of California, Los Angeles

John Dunlosky, Kent State University

Joe Kim, McMaster University

Jim Cooke, University of California, San Diego

Jeri Little, California State University, East Bay

Mark McDaniel, Washington University in St. Louis

Tim Rickard, University of California, San Diego

Josh Samani, University of California, Los Angeles

Faria Sana, Athabasca University